Laurel and Hardy

Laurel and Hardy were one of the most popular comedy teams of the early to mid Classical Hollywood era of American cinema. Composed of thin, English-born Stan Laurel (1890–1965) and heavy, American-born Oliver Hardy (1892–1957) they became well known during the late 1920s to the mid-1940s for their work in motion pictures; the team also appeared on stage throughout America and Europe.

The two comedians first worked together on the silent film The Lucky Dog. After a period appearing separately in several short films for the Hal Roach studio during the 1920s, they began appearing in movie shorts together in 1926.[1] Laurel and Hardy officially became a team the following year, and soon became Hal Roach's most lucrative stars. Among their most popular and successful films were the features Sons of the Desert (1933), Way Out West (1937), and Block-Heads (1938)[2] and the shorts Big Business (1929), Liberty (1929), and their Academy Award–winning short, The Music Box (1932).[3]

The pair left the Roach studio in 1940, then appeared in eight "B" comedies for 20th Century Fox and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer from 1941 to 1944.[4] Disappointed in the films in which they had little creative control, from 1945 to 1950 the team did not appear on film and concentrated on their stage show, embarking on a musical hall tour of England, Ireland and Scotland.[4] They made Atoll K, a French/Italian production and their last film, in 1950/1951, before retiring from the screen. In total they appeared together in 106 films. They starred in 40 short sound films, 32 short silent films and 23 full length feature films, and in the remaining 11 films made guest or cameo appearances.[5]

Contents |

Before the teaming

Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel (June 16, 1890 – February 23, 1965) was born Arthur Stanley Jefferson in Ulverston, Lancashire (now Ulverston, Cumbria), England. His father, Arthur J. "A.J." Jefferson, was a showman who served as actor, director, playwright and theatrical entrepreneur in many northern English cities.

Laurel began his career in the Glasgow Britannia Theatre of Varieties and Alhambra Theatre Glasgow at the age of 16, where he crafted a comedy act largely derivative of famous music hall comedians of the day, including George Robey and Dan Leno. He gradually worked his way up the ladder of supporting roles until he became the featured comedian, as well as an understudy to Charlie Chaplin in Fred Karno's comedy company.[6] He emigrated to America in 1912 where he decided to change his name; he worried that "Stanley Jefferson" was too long to fit onto posters. He shortened it to "Stan" and added "Laurel" at the suggestion of his superstitious vaudeville partner, Mae Dahlberg who fretted that his original stage name was composed of 13 letters.[7]

Making his first film appearance in Nuts in May (1917), Laurel continued to make more than 50 other silent films for various producers.[8] At first he experienced only modest success as a solo comedian. Producer Hal Roach later attributed this to the difficulty in photographing Laurel's pale blue eyes on early pre-panchromatic film stock, perhaps giving the appearance of blindness (which, in his earliest films, Laurel tried to remedy by adding heavy defining makeup around his eyes). Moreover, Laurel did not have an identifiable or easily marketable screen character, like that of Chaplin, Harold Lloyd or Buster Keaton.

It was only when Laurel began appearing in satires of popular screen dramas that audiences really took notice of him. Between 1922 and 1925 he starred in a number of films including Mud and Sand (1922) (a parody of Blood and Sand, featuring Stan as "Rhubarb Vaselino") and Dr. Pyckle and Mr. Pryde (1925) (with Stan playing both the gentle doctor and the manic monster). Many of these comedies had crazy visual gags along with Laurel's eccentric pantomime, establishing the star as an inspired "nut comic."

Oliver Hardy

Oliver Hardy (January 18, 1892 – August 7, 1957) was born Norvell Hardy in Harlem, Georgia.[9] As a tribute to his father (who died when Norvell was very young), he took his father's first name (although not legally), henceforth calling himself "Oliver Norvell Hardy." His offscreen nicknames were "Ollie" and "Babe."

Hardy's nickname "Babe" originated during his (pre-Laurel) early silent film career. Hardy was a frequent visitor to an Italian barbershop near the Lubin Studios in Jacksonville, Florida where he worked. After cutting his hair and giving him a shave, the barber would then pat his face with talcum powder whilst saying, "That's nice a baby!" With the barber's Italian accent, "baby" sounded like "Babe." That nickname stuck with Hardy for the rest of his life. Hardy was billed as "Babe Hardy" in his early films.[10] In some of the duo's first silent films, Laurel can be seen mouthing the word "Babe" when calling out to Ollie.

By his late teens, Hardy was a popular stage singer, and he operated his own movie house in Milledgeville, Georgia, the Palace Theater, financed partially by his mother.[11] Seeing film comedies inspired him with an urge to take up comedy himself and in 1913, he began working with Lubin Motion Pictures in Jacksonville, Florida. He started out by helping around the studio with lights, props and other duties, gradually learning the craft as a script-clerk.[11] Around the same time, he married his first wife, Madelyn Salosihn.[12]

In 1914, Babe acted in his first film called Outwitting Dad.[10] Between 1914 and 1916, Babe made 177 shorts with the Vim Comedy Company, which were released up to the end of 1917.[13] Exhibiting a versatility in playing heroes, villains and even female characters, Hardy became much in demand as a supporting actor, comic villain or second banana. For the next 10 years he memorably assisted star comics Billy West, a Charlie Chaplin imitator, Jimmy Aubrey, Larry Semon and Charley Chase.[14] In total, Hardy starred or co-starred in more than 250 silent shorts, about 150 of which have been lost. While in New York, his abortive effort to enlist in 1917 led him and his wife, Madelyn, to seek new opportunities in California.[15] Hardy became a member of Hal Roach's stock company when he began working regularly with Stan Laurel.

History

Laurel and Hardy: Hal Roach years

Laurel and Hardy appeared for the first time together in The Lucky Dog (1921). In this lobby card scene, Stan Laurel (left), is attacked by Oliver Hardy (above) as Jack Lloyd spots that Stan's faithful dog has retrieved Oliver's lit stick of dynamite.

|

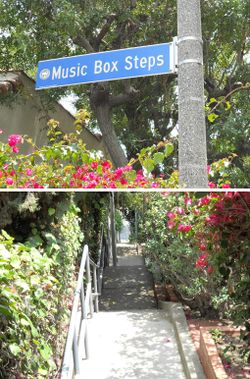

The location used in the Academy Award winning The Music Box (1932), in which the team must climb a steep flight of outdoor steps to deliver a piano, still exists in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles. It is considered a landmark and is marked with a plaque and sign.

|

Laurel and Hardy in their 1939 feature film The Flying Deuces.

|

The first film pairing of the two comedians (albeit as separate performers) took place in The Lucky Dog, produced in 1919 by Sun-Lite Pictures and released in 1921.[16] Several years later, both comedians appeared in the Hal Roach production 45 Minutes from Hollywood (1926). Their first "official" film together was Putting Pants on Philip, although their first appearance as the now familiar "Stan and Ollie" characters was The Second Hundred Years (June 1927), directed by Fred Guiol and supervised by Leo McCarey, who suggested that the performers be teamed permanently.

Hal Roach kept them a team for the next decade, making silent shorts, talking shorts, and feature films. While most silent-film actors saw their careers decline with the advent of sound, Laurel and Hardy made a successful transition in 1929 with the short Unaccustomed As We Are. Laurel's English accent and Hardy's Southern American accent and singing brought new dimensions to their characters. The team also proved skillful in their melding of visual and verbal humor, adding dialogue that served to enhance rather than replace their popular sight gags.

Laurel and Hardy's shorts, produced by Hal Roach and initially released through Pathé and then in 1929 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, were among the most successful in the business. Most of the shorts ran two reels (10 minutes per reel), although several ran three reels long, and one, Beau Hunks, was four reels long. In 1929, they appeared for the first time in a feature as one of the acts in The Hollywood Revue of 1929 and the following year, they appeared as the comic relief in a lavish all-Technicolor musical feature entitled: The Rogue Song. This film marked their first appearance in color. Considered a "lost film", only a few fragments of this production have survived, along with the complete soundtrack. In 1931, Laurel and Hardy's first starring feature was released, Pardon Us. Following its success, the duo made fewer shorts in order to concentrate on feature films, which included Pack Up Your Troubles (1932), Fra Diavolo (or The Devil's Brother, 1933), Sons of the Desert (1933), and Babes in Toyland (1934).[1] Their classic short The Music Box, released in 1932, won the first Academy Award for Best Short Subject, (Comedy).

Because the popularity of the double feature diminished the demand for short subjects, Hal Roach cancelled all of his shorts series, save for Our Gang. The final short in the Laurel and Hardy series was 1935's Thicker than Water. The duo's subsequent feature films included Bonnie Scotland (1935), The Bohemian Girl (1936), Our Relations (1936), Way Out West (1937) (which includes the famous song "Trail of the Lonesome Pine"), Swiss Miss (1938) and Block-Heads (1938).

Style of comedy and notable routines

The humor of Laurel and Hardy was generally visual with slapstick used for emphasis. They often had physical arguments with each other, which were quite complex and involved cartoon violence. Their characters preclude them from making any real progress in even the simplest endeavors. Much of their comedy involves milking a joke, where a simple idea provides a basis from which to build several gags. Many of their films have extended sequences constructed around a single problem the pair is facing, without following a defined narrative. Laurel did most of the planning and construction of gags while Hardy was more limited in his contributions to the comedy routines.[12]

A common routine the team often performed was a "tit-for-tat" fight with an adversary. Typically, Laurel and Hardy accidentally damaged someone else's property. The injured party would retaliate by ruining something belonging to Laurel or Hardy, who would calmly survey the damage and find something else to vandalize. The conflict would escalate until both sides were simultaneously destroying property in front of each other. An early example of the routine occurs in their classic short, Big Business (1929), which was added to the Library of Congress as a national treasure in 1992, and one of their short films, which revolves entirely around such an altercation, was titled Tit for Tat (1935).

In some cases, their comedy bordered on the surreal, a style Stan Laurel called "white magic." [17] For example, in Way Out West (1937), Laurel clenches his fist and pours tobacco into it, as if it were a pipe. Then, he flicks his thumb upward as if he held a lighter. His thumb ignites, and he matter-of-factly lights his "pipe." The amazed Hardy, seeing this, would unsuccessfully attempt to duplicate it throughout the rest of the film. Much later in the film, Hardy finally succeeds - only to be terrified when his thumb catches fire.

Rather than showing Hardy suffering the pain of misfortunes such as falling down stairs or being beaten by a thug, banging and crashing sound effects were often used so the audience could visualize the scene for themselves. Routines frequently performed by Laurel were a high pitched whooping when in peril and crying like an infant when being berated by Hardy. Hardy often looked directly at the camera, breaking the fourth wall, to express his frustration with Laurel to the film audience.

On-screen characterizations

Laurel and Hardy's onscreen personas are of two dim but eternally optimistic men, secure in their perpetual and impregnable innocence. Their humor is physical, but their accident-prone buffoonery is distinguished by their affable personalities and mutual devotion; essentially "children" in an adult world.

Laurel and Hardy had an inherent physical contrariety which was enhanced with small touches. Laurel kept his hair short on the sides and back, but let it grow long on top to create a natural "fright wig" through his inveterate gesture of scratching his head at moments of shock or wonderment and simultaneously pulling up his hair. In contrast, Hardy's thinning hair was pasted on his forehead in spit curls and he wore a toothbrush moustache. To achieve a flat-footed walk, Laurel removed the heels from his shoes (usually Army shoes). Stan Laurel was of average height and weight, but appeared small and slight next to Oliver Hardy, who was 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) tall[18] and weighed about 280 lb (127 kg) in his prime. Both wore Bowler hats, with Laurel's being narrower than Hardy's, and with a flattened brim. The characters' normal attire also called for wing collar shirts, with Hardy wearing a standard neck tie which he would twiddle and Laurel a bow tie. Hardy's sports jacket was too small for him and done up with one straining button, whereas Laurel's double breasted jacket was loose fitting.

Part of Laurel and Hardy's onscreen images called for their faces to be filmed flat, without any shadows or dramatic lighting. To invoke a traditional clown-like appearance, both comedians wore a light pancake makeup on their faces, and Roach's cameramen, such as Art Lloyd and Francis Corby, were instructed to light and film a scene so that facial lines and wrinkles would be "washed out." Art Lloyd was once quoted as saying, "Well, I'll never win an Oscar, but I'll sure please Stan Laurel."

Offscreen, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were quite the opposite of their movie characters: Laurel was the industrious "idea man," while Hardy was more easygoing.[19] Although Hal Roach employed writers and directors such as H.M. Walker, Leo McCarey, James Parrott, James W. Horne, and others on Laurel and Hardy films, Laurel would rewrite entire sequences or scripts, have the cast and crew improvise on the soundstage, and meticulously review the footage for editing, often moonlighting to achieve all of these tasks. While Hardy did contribute to the routines,[19] he was generally content to follow Laurel's lead and spent most of his free time on hobbies such as golf.

Later films

By 1936, although the relationship between Laurel and Hardy remained strong, Laurel's dealings with producer Roach became strained amid a tangle of artistic differences. Roach insisted that his feature-length comedies should also contain musical numbers and/or subplots. (Roach always contended that if you watched any comedian for an hour at a time, "you'd be bored to hell with him.") Laurel maintained that such padding distracted from the team's comedy. Because of this friction, extended stand-off periods became common during the late 1930s, with Roach occasionally threatening to pair Hardy with someone else.

Laurel countered Roach's announcement with one revealing his own plans. In October 1938, Roach's old rival Mack Sennett announced that he had signed Laurel to star in comedy features for his new Sennett Pictures Corporation Studio.[20] Those films were not made, since by April 1939 the dispute between Laurel and Roach was settled and the comedy team was again intact for further work with Roach. They made two more films for Roach, A Chump at Oxford (filmed in 1939, released 1940) and Saps at Sea (1940). Both of these films were released through United Artists, as Roach's distribution arrangement with MGM had ended in 1938. As their new agreement with Roach was non-exclusive, Laurel and Hardy also starred in The Flying Deuces, a feature-length remake of Beau Hunks produced and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

Hoping for greater artistic freedom, Laurel and Hardy split with Roach and signed with major studios 20th Century-Fox and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. However, the working conditions were now completely different, as they were hired only as actors, relegated to the B-film divisions, and initially not allowed to improvise or contribute to the scripts. When the films proved popular, the studios allowed the team more input with Laurel and Hardy starring in eight features through 1944. These films, while not considered the team's best, were extremely successful. Budgeted at $250,000 to $300,000 each, the films earned millions at the box office. The films were so profitable that Fox kept making Laurel and Hardy comedies after discontinuing its other "B" series.

After spending the rest of the 1940s performing on stage in Europe, Laurel and Hardy made one final film together in 1950. Atoll K, later reissued in abridged form in the United States as Utopia, released in 1954, was a French-Italian co-production directed by Leo Joannon, which was plagued by language barriers, production problems, and both Laurel and Hardy's grave health issues during shooting. Hardy began to lose weight precipitously and developed an irregular heartbeat while Laurel experienced painful prostate complications.[21] Critics were disappointed with its storyline, English dubbing, and Laurel's sickly physical appearance with his weight down to 114 pounds (52 kg; 8.1 st).[18] The film was not a success, and brought an end to Laurel and Hardy's film careers, yet due to copyright problems in the United States, the film became available under the provisions of public domain, and was widely distributed by small distributors, remaining the most easily available of the team's features.[21]

Final years

After Atoll K, Laurel and Hardy took several months off, so that Laurel could recuperate. Upon their return to the European stage, they undertook a successful series of public appearances in short sketches Laurel had written: "A Spot of Trouble" (in 1952) and "Birds of a Feather" (in 1953).[22]

On December 1, 1954, the team made their only American television appearance, surprised by Ralph Edwards on his live NBC-TV program, This Is Your Life. Lured to the Knickerbocker Hotel as a subterfuge for a business meeting with producer Bernard Delfont, the doors opened to their suite #205, flooding the room with light and the voice of Ralph Edwards. At first the boys reacted incredulously, like deer caught in headlights. From the moment the boys realized they're on camera, Stan smiles graciously, and did so all night. Ollie comically drinks the rest of his "beverage" before hurriedly being ushered to an awaiting car on Ivar Ave, to the Hollywood Blvd.'s El Capitan theatre down the street, for their night of tribute. The telecast was preserved on a kinescope and later released on home video. Partly due to the positive response from the television broadcast, the pair was renegotiating with Hal Roach Jr. for a series of color NBC television specials to be called Laurel and Hardy's Fabulous Fables. However, plans for the specials were shelved, as the aging comedians suffered from declining health.[22]

In 1955, Laurel and Hardy made their final public appearance together, taking part in a BBC television program about the Grand Order of Water Rats, the British variety organization, titled This is Music Hall. Laurel and Hardy provide a filmed insert during which they reminisce about their friends in British variety. They made their final appearance on camera in 1956 in a home movie titled "One Moment Please". The film was shot by a family friend at Stan's home, it is without audio and lasts three minutes.

Under doctor's orders to improve a heart condition, Hardy lost over 100 pounds (45 kg; 7.1 st) in 1956. Several strokes (that some doctors partly attribute to the rapid weight loss) resulted in loss of mobility and speech. He died of a major stroke on August 7, 1957. Longtime friend Bob Chatterton said Hardy weighed just 138 pounds (63 kg; 9.9 st) at the time of his death. A depressed Laurel did not attend his partner's funeral, due to his own ill health, explaining his absence with the line "Babe would understand." Hardy was laid to rest at Pierce Brothers Valhalla Memorial Park, North Hollywood.[23]

Just after Hardy's death, Laurel and Hardy returned to movie theaters, as clips of their work were featured in Robert Youngson's silent-film compilation The Golden Age of Comedy. For the remaining eight years of his life, Stan Laurel refused to perform, even turning down Stanley Kramer's offer to make a cameo in his landmark 1963 movie, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. In 1960, Laurel was given a special Academy Award for his contributions to film comedy. Despite not appearing onscreen after Hardy's death, Laurel did contribute gags to several comedy filmmakers. Most of his writing was in the form of correspondence; he insisted on answering every fan letter personally. Late in life, he hosted many visitors of the new generation of comedians and celebrities, including Dick Cavett, Jerry Lewis, Peter Sellers, Marcel Marceau and Dick Van Dyke. Laurel lived until 1965, surviving to see the duo's work rediscovered through television and classic film revivals. He died in Santa Monica, and is buried at Forest Lawn-Hollywood Hills in Los Angeles, California.[24]

Foreign language films

A number of their films were reshot with Laurel and Hardy talking in Spanish, Italian, French or German. The plots for these films were similar to the English language version although the supporting cast were often native language actors. Laurel and Hardy couldn't speak a foreign language and they received voice coaching to reproduce their lines. Pardon Us (1931) was reshot in all 4 foreign languages. Blotto (1930), Chickens Come Home (1931) and Below Zero (1930) had a French and Spanish version. These film versions helped to boost the duo’s popularity internationally.

In Spanish they are known as "El Gordo y El Flaco" ("the fat one and the skinny one"). In Swedish they are known as "Helan & Halvan" ("The Whole One" and "The Half One"). In German they used to be known as "Dick und Doof" ("Fatty & Idiot"), and since the 1970s as "Stan & Ollie" or under their English name.

Supporting cast

Laurel and Hardy's films included a memorable supporting cast, some of whom appeared regularly.

- Harry Bernard, played bit parts as waiter, bartender and cop.

- Strong willed Mae Busch played a formidable Mrs. Hardy, and some other characters.

- Baldwin Cooke played bit parts as waiter, bartender and cop.

- James Finlayson, a small, balding, moustachioed Scotsman known for displays of indignation and squinting "double takes", made 33 appearances.

- Beautiful Anita Garvin was a memorable Mrs. Laurel.

- Billy Gilbert, character actor great and Hal Roach staple, made many appearances—most notably in the classic The Music Box.

- Charlie Hall, who usually played angry "little men", appeared nearly 50 times.

- "Blonde bombshell" Jean Harlow had a small role in their short Double Whoopee (1929) and two other films, before her breakout stardom.

- Arthur Housman made memorable appearances as a comic drunk.

- Edgar Kennedy master of the "slow burn", often appeared as a cop, or a hostile neighbor or relative.

- Walter Long played grizzled, physically threatening villains.

- Grim-faced Sam Lufkin appeared several times.

- The diminutive Daphne Pollard was featured.

- The English actor Charley Rogers appeared several times.

- Tiny Sandford was a very tall and burly man who played authority figures, notably cops.

- Cross-eyed Ben Turpin made two memorable appearances.

Lost films

Most of the Laurel and Hardy films survive, and have never gone out of circulation permanently. Three of their 106 films are considered lost, as they have not been seen in full since the 1930s. The silent Hats Off (1927) has vanished completely. The first half of Now I'll Tell One (1927) is lost and the second half has yet to be released on video. In the operatic Technicolor musical The Rogue Song (1930) Laurel and Hardy appear in 10 sequences, only one of which is known to exist. Two other films have missing content although they aren't considered lost. Duck Soup (1927) was considered lost until a print was discovered in the mid-1970s, this print appears to be missing a few minutes of footage at the beginning and end. The Battle of the Century (1927) has several minutes of missing footage bridging the first and second halves, and the final half-minute is also missing.

Music

The duo's famous signature tune, known variously as "The Cuckoo Song", "Ku-Ku", or "The Dance of the Cuckoos", was composed by Roach musical director Marvin Hatley as the on-the-hour chime for the Roach studio radio station. Laurel heard the tune on the station, and asked Hatley to use it as the Laurel and Hardy theme song. In Laurel's eyes, the song's melody represented Hardy's character (pompous and dramatic), while the harmony represented Laurel's own character (somewhat out of key, and only able to register two notes: "coo-coo"). The original theme, recorded by two clarinets in 1930, was re-recorded with a full orchestra in 1935. Although uncredited, the composer Leroy Shield composed the great majority of the music used in the Laurel and Hardy films. A compilation of songs from their films titled Trail of the Lonesome Pine was released in 1975.

Influence and legacy

Catchphrases

The catchphrase most used by Laurel and Hardy on film is:

| “ | Well, that's another nice mess you've gotten me into! | ” |

The phrase was first used in The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case (1930). In popular culture the catchphrase is often misquoted as "Well, here's another fine mess you've gotten me into." The misquoted version of the phrase was very rarely used by Ollie; the misunderstanding stems from the title of Another Fine Mess (1930).[25] Numerous variations of the quote appeared on film. In Chickens Come Home (1931), Ollie says impatiently to Stan, "Well...." with Stan replying, "Here's another nice mess I've gotten you into." In Thicker Than Water (1935) and The Fixer-Uppers (1935) the phrase becomes "Well, here's another nice kettle of fish you pickled me in!". In Saps at Sea (1940) it becomes "Well, here's another nice bucket of suds you've gotten me into!".

| “ | D'oh! | ” |

D'oh!" is a catchphrase used by James Finlayson, the mustachioed Scottish actor who appeared in 33 Laurel and Hardy films. The word was used as a replacement for "Damn!". His catchphrase was the inspiration for "D'oh!" as spoken by the fictional character Homer Simpson in the long running animated comedy The Simpsons. The Simpson's first intentional use of "d'oh!" occurred in the Ullman short "Punching Bag" (1988). [26]

The Sons of the Desert

The official Laurel and Hardy appreciation society is known as The Sons of the Desert, after a fraternal society in their film of the same name (1933). It was founded in New York City in 1965 by Laurel & Hardy biographer John McCabe, Orson Bean, Al Kilgore, Chuck McCann and John Municino; with the sanction of Stan Laurel. Since the group's inception, well over 150 chapters of the organization have formed across North America, Europe and Australia. An Emmy-winning film documentary about the group, Revenge of the Sons of the Desert, has been released on DVD as part of The Laurel and Hardy Collection, Vol. 1.

Posthumous revivals

Since the 1930s, the works of Laurel and Hardy have been re-released in numerous theatrical reissues, television revivals (broadcast, especially public television, and cable), 16mm and 8mm home movies, feature-film compilations, and home video. After Stan Laurel's death in 1965, there were two major motion-picture tributes: Laurel and Hardy's Laughing '20s, Robert Youngson's compilation of the team's silent-film highlights; and The Great Race, a large-scale salute to slapstick which director Blake Edwards dedicated to "Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy." For many years the duo were impersonated by Jim MacGeorge (as Laurel) and Chuck McCann (as Hardy) in television commercials for various products.[27]

Merchandiser Larry Harmon claimed ownership of Laurel's and Hardy's likenesses, and issued Laurel and Hardy toys and colouring books. He co-produced a series of Laurel and Hardy cartoons in 1966 with Hanna-Barbera Productions.[28] His animated versions of Laurel and Hardy also guest-starred in a 1972 episode of Hanna-Barbera's The New Scooby-Doo Movies. In 1999, Harmon produced a direct-to-video feature, the live-action comedy The All-New Adventures of Laurel and Hardy: For Love or Mummy, with actors Bronson Pinchot and Gailard Sartain playing the lookalike nephews of the original Laurel and Hardy, Stanley Thinneus Laurel and Oliver Fatteus Hardy.[29]

Colorized versions

Many Laurel and Hardy films have been colorized. Helpmates (1932) was the first film to undergo the process, it was experimented upon by Colorization Inc., a subsidiary of Hal Roach Studios in 1983. Colorization became a success for the studio and Helpmates was released on home video with the colorized version of The Music Box (1932) in 1986. The technology for this process was inferior compared to today's digital colorization technology. There were numerous continuity errors and garish color design choices. However the most significant criticism that these versions received revolved around their editing, whole scenes were altered or deleted altogether, changing the character of the film.

In other popular culture

- There are two Laurel and Hardy museums, one in Laurel's birthplace, Ulverston, United Kingdom,[30], and the other in Hardy's birthplace, Harlem, Georgia, United States [31]

- Laurel and Hardy's likenesses have made frequent "cameo appearances" in animated cartoons and comic strips since the 1930s. They featured in a Laurel and Hardy cartoon series by Hanna-Barbera and made a guest appearance in The New Scooby-Doo Movies. From Mickey Mouse to Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies to Woody Woodpecker, caricatured versions of the comedians appeared as walk-on characters and sometimes in supporting roles in cartoons from the Golden Age of American animation. Laurel and Hardy have also turned up in more recent works such as the Asterix album Obelix and Co., Mark Dindal's animated film Cats Don't Dance (1997), Berkeley Breathed's comic strip Bloom County, Gary Larson's comic strip The Far Side and the The Simpsons episode The Wandering Juvie.

- In one of the few instance of incorporating the famous duo's visages into popular literature, author/illustrator Maurice Sendak's In the Night Kitchen (1970)[32] showed three identical Oliver Hardy figures as bakers preparing cakes for the morning in his award-winning children's book and is treated as a clear example of "interpretative illustration" wherein the comedians' inclusion harkened back to the author's own childhood. Sendak described his early upbringing as sitting in movie houses fascinated by the Laurel and Hardy comedies.[33][34]

- Laurel and Hardy were featured alongside many other celebrities in cutout form for the cover of the Beatles's 1967 masterpiece album, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Of the two, Stan is more recognizable.

- In 1976, STV (Scottish Television) produced a half-hour play by Alex Norton called Stan's First Night, about a 16-year-old Stan Jefferson's (Stan Laurel's real name) first appearance on stage at the Panopticon variety theatre in Glasgow.

- Kurt Vonnegut's 1976 novel Slapstick not only owes its title to the "grotesque situational poetry" of Laurel and Hardy's film comedies, but also bears the dedication to "the memory of Arthur Stanley Jefferson and Norvell Hardy, two angels of my time" and features the 1975 caricature of the pair by Al Hirschfeld on the page opposite.

- Based on a 2005 poll of the top 50 comedians featured in The Comedian's Comedian, a TV documentary broadcast on UK's Channel 4 on January 1, 2005, the duo was voted the seventh greatest comedy act ever by fellow comedians and comedy insiders, making them the most popular double act on the list.[35]

- In 2006, BBC in the UK broadcast a drama Stan about Laurel's final visit to see the dying Hardy. The TV programme derived from a radio play first broadcast in 2004. Both radio and TV versions were written by Neil Brand.

- In Indian (hindi) comicstrip culture, the most well known pair of foolhardy jokers: Mottoo and Patlu मोटू और पतलू (The Fat Guy and the Thin Guy) were inspired by Laurel and Hardy.

See also

- Laurel and Hardy films

- Filmography of Oliver Hardy

- Filmography of Stan Laurel

- Double act

References

- Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Smith 1984, p. 24.

- ↑ "Best Laurel And Hardy Titles: Highest rated features at IMDb." IMDb. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Best Laurel And Hardy Titles: Highest rated shorts at IMDb." IMDb. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McGarry 1992, p. 67.

- ↑ McCabe 1975, p. 17.

- ↑ Louvish 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Bergen 1992, p. 20.

- ↑ Louvish 2001, p. 118. Note: Nuts in May has disappeared but portions of it were apparently incorporated in the later Mixed Nuts (1925).

- ↑ Louvish 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McCabe 1989, p. 19.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bergen 1992, p. 26.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Everson 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ McCabe 1989, p. 30.

- ↑ Louvish 2001, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ McCabe 1989, p. 32.

- ↑ Everson 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ McCabe 1975, p. 18.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Mitchell, Glenn. The Laurel & Hardy Encyclopedia. London: Batsford, 1995. ISBN 0-7134-7711-3.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gehring 1990, p. 5.

- ↑ Pryor, Thomas M. "Laurel to Make Film Series for Sennett". The New York Times, September 12, 1938. Excerpt: "...Mack Sennett announced that he had signed Stan Laurel to star in a series of films he will make with a new producing company to be known as Sennet Pictures Corporation. Laurel was under contract to Hal Roach as member of the Laurel and Hardy comedy team, until last month, when Roach broke up the combination, alleging that Laurel violated his contract, and substituted Harry Langdon as Hardy's mate..."

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 McGarry 1992, p. 73.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 McCabe 1975, p. 398.

- ↑ Smith 1984, p. 191.

- ↑ Smith 1984, p. 187.

- ↑ Andrews 1997, p. 389.

- ↑ "What’s the story with... Homer’s D’oh!". The Herald, Glasgow, July 21, 2007, p. 15. Retrieved: July 25, 2010.

- ↑ McCann, Chuck. "Laurel & Hardy Tribute." chuckmccann.net: Chuck McCann, November 30, 2007. Retrieved: Marcn 1, 2010.

- ↑ Krurer, Ron. "Laurel and Hardy cartoons by Hanna-Barbera." toontracker.com. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "The All New Adventures of Laurel & Hardy in 'For Love or Mummy' (1999)." IMDb. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Laurel & Hardy Museum: Ulverston akedistrictletsgo.co.uk, June 2004. Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Root, Robin. "Laurel and Hardy Museum and Harlem, Georgia Visitor Info Center." www.laurelandhardymuseum Retrieved: March 1, 2010.

- ↑ Sendak, Maurice. In the Night Kitchen. New York: HarperCollins, First edition 1970. ISBN 0-06026-668-6.

- ↑ Lanes, Selma G. The Art of Maurice Sendak. New York: Harry N. Abrams; 2nd revised edition, 1998, first edition, 1980, p. 47. ISBN 0-81098-063-0.

- ↑ Salamon, Julie. "Sendak in All His Wild Glory." New York Times, April 15, 2005. Retrieved: May 28, 2008.

- ↑ "The List." The Comedian's Comedian, 2005. Retrieved: 3 March 2010.

- Bibliography

- Andrews, Robert, Famous Lines: A Columbia Dictionary of Familiar Quotations. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-23110-218-6.

- Anobile, Richard J., ed. A Fine Mess: Verbal and Visual Gems from The Crazy World of Laurel & Hardy. New York: Crown Publishers. 1975. ISBN 0-51752-438-4. (Laurel & Hardy film frames and dialogue reproduced in book form)

- Barr, Charles. Laurel & Hardy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1974, first edition 1967. ISBN 0-520-00085-4. (Insights and observations about the screen characters portrayed by Laurel and Hardy)

- Bergen, Ronald. The Life and Times of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Smithmark, 1992. ISBN 0-8317-5459-1. (Career overview and numerous large-format color and monochrome photographs)

- Brooks, Leo M. The Laurel & Hardy Stock Company. Hilversum, Netherlands: Blotto Press. 1997. ISBN 90-9010461-5.

- Byron, Stuart and Elizabeth Weis, eds. The National Society of Film Critics on Movie Comedy. New York: Grossman/Viking, 1977. ISBN 978-0670491865.

- Crowther, Bruce. Laurel and Hardy: Clown Princes of Comedy. New York: Columbus Books, 1987. ISBN 978-0862873448.

- Durgnat, Raymond. "Beau Chumps and Church Bells" (essay)." The Crazy Mirror: Hollywood Comedy and the American Image. New York: Dell Publishing, 1970. ISBN 978-0385281843.

- Everson, William K. The Complete Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel, 2000, 1967. ISBN 0-8065-0146-4. (First book-length examination of the individual films)

- Everson, William K. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. ISBN 978-0870705595. (Digest overview of producer Hal Roach's films, published in connection with a film retrospective)

- Gehring, Wes D. Film Clowns of the Depression: Twelve Defining Comic Performances. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007. ISBN 978-0786428922.

- Gehring, Wes D. Laurel & Hardy: A Bio-Bibliography. Burnham Bucks, UK: Greenwood Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0313251726.

- Guiles, Fred Lawrence. Stan: The Life of Stan Laurel. New York: Stein & Day, 1991, first edition 1980. ISBN 978-0812885286.

- Harness, Kyp. The Art of Laurel and Hardy: Graceful Calamity in the Films. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2006. ISBN 0-78642-440-0. (Critical assessment of the comedians and their films)

- Kanin, Garson. Together Again!: Stories of the Great Hollywood Teams. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1981. ISBN 978-0385174718.

- Kerr, Walter. The Silent Clowns. New York: Da Capo Press, 1990, first edition 1975, Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0306803871.

- Lahue, Kalton C. World of Laughter: The Motion Picture Comedy Short, 1910-1930. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966. ISBN 978-0806106939. (History of silent-comedy films and producers, including Hal Roach and Laurel and Hardy)

- Louvish, Simon. Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy. London: Faber & Faber, 2001. ISBN 0-571-21590-4. (Biography, with new research revealing more about the comedians' personal lives)

- MacGillivray, Scott. Laurel & Hardy: From the Forties Forward, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. New York: iUniverse, 2009; first edition Lanham, Maryland: Vestal Press, 1998. ISBN 1-440172-39-0. (Discussion of the post-1940 films, unrealized projects, revivals, compilations and TV, home-movie and video releases)

- Maltin, Leonard. The Great Movie Comedians. New York: Crown Publishers, 1978. ISBN 978-0517532416. (Discussion of famous film comedians, including Laurel and Hardy)

- Maltin, Leonard. The Laurel & Hardy Book (The Curtis Films Series). Sanibel Island, FL: Ralph Curtis Books, 1973.

- Maltin, Leonard. Movie Comedy Teams. New York: New American Library, 1985, first edition 1970. ISBN 978-0452256941.

- Maltin, Leonard, Selected Short Subjects (first published as The Great Movie Shorts. New York: Crown Publishers, 1972.) New York: Da Capo Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0452256941

- Marriot, A.J. Laurel & Hardy: The British Tours. Hitchen, Herts, UK: AJ Marriot, 1993. ISBN 0-9521308-0-7.

- Mast, Gerald. The Comic Mind: Comedy and the Movies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979, first edition 1973. ISBN 978-0226509785.

- McCabe, John. Babe: The Life of Oliver Hardy. London: Robson Books, 2004, first edition 1989, Citadel. ISBN 1-86105-781-4. (In-depth biography of Oliver Hardy, drawing upon unused material from McCabe's earlier biography)

- McCabe, John. The Comedy World of Stan Laurel. New York: Robson Press, 1990, first edition 1974, Doubleday & Co. ISBN 978-0940410237.

- McCabe, John. Mr. Laurel & Mr. Hardy: An Affectionate Biography. London: Robson Books, 2004, first edition 1961, 1966, Doubleday & Co. ISBN 1-86105-606-0. (The authorized Laurel & Hardy biography, containing firsthand recollections by Laurel and Hardy themselves, and quotes from family members and colleagues; Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy: An Affectionate Biography title changed in 1966 edition to Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy: An Affectionate Biography of Laurel and Hardy and changed again in 1976 and 2004 reprint editions.)

- McCabe, John with Al Kilgore and Richard W. Bann. Laurel & Hardy. New York: Bonanza Books, 1983, first edition 1975, E.P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0491017459. (Photographs and text replicating the sequences seen in the films)

- McCaffrey, Donald W. "Duet of Incompetence" from The Golden Age of Sound Comedy: Comic Films and Comedians of the Thirties. New York: A.S. Barnes, 1973. ISBN 978-0498010484.

- McGarry, Annie. Laurel & Hardy. London: Bison Group, 1992. ISBN 0-86124-776-0. (Brief overview of the films, drawing upon previously published sources)

- McIntyre, Willie. The Laurel & Hardy Digest: A Cocktail of Love and Hisses. Ayrshire, Scotland: Willie McIntyre, 1998. ISBN 978-0953295807.

- Mitchell, Glenn. The Laurel & Hardy Encyclopedia. New York: Batsford, 1995. ISBN 0-7134-7711-3.

- Nollen, Scott Allen. The Boys: The Cinematic World of Laurel and Hardy. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0786411153.

- Robb, Brian J. The Pocket Essential Laurel & Hardy. Manchester, UK: Pocket Essentials, 2008. ISBN 978-1842432853.

- Robinson, David. The Great Funnies: A History of Film Comedy. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1969. ISBN 978-0289796436.

- Sanders, Jonathan. Another Fine Dress: Role Play in the Films of Laurel and Hardy. London: Cassell, 1995. ISBN 978-0304331963.

- Scagnetti, Jack. The Laurel & Hardy Scrapbook. New York: Jonathan David Publishers, 1982. ISBN 978-0824602789.

- Smith, Leon. Following the Comedy Trail: A Guide to Laurel & Hardy and Our Gang Film Locations. Littleton, Massachusetts: G.J. Enterprises, 1984. ISBN 978-0938817055.

- Skretvedt, Randy. Laurel and Hardy: The Magic Behind the Movies (2nd ed.) Anaheim, California: Past Times Publishing Co., 1996, first edition 1987, Moonstone Press. ISBN 0-940410-29-X. (Film-by-film analysis, with detailed behind-the-scenes material and numerous quotes from colleagues.)

- Staveacre, Tony. Slapstick!: The Illustrated Story. London: Angus & Robertson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 978-0207150302.

- Stone, Rob et al. Laurel or Hardy: The Solo Films of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy. Manchester, New Hampshire: Split Reel, 1996. ISBN 0-965238-407. (Exhaustive study of the comedians as solo performers, 1913–26)

- Ward, Richard Lewis. A History of the Hal Roach Studios. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0809326372.

- Weales, Gerald. Canned Goods as Caviar: American Film Comedy of the 1930s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0226876641.

External links

- Stan Laurel at the Internet Movie Database

- Oliver Hardy at the Internet Movie Database

- The Laurel and Hardy Magazine website

- The official Sons of the Desert website

- The official Laurel and Hardy website

- The Laurel and Hardy Forum

- Laurel and Hardy Online

- The Charlie Hall Picture Archive

- The Nutty Nut News Network

- The official Leroy Shield website

- Laurel and Hardy at Find a Grave

- Laurel and Hardy at Find a Grave

|

|||||||||||